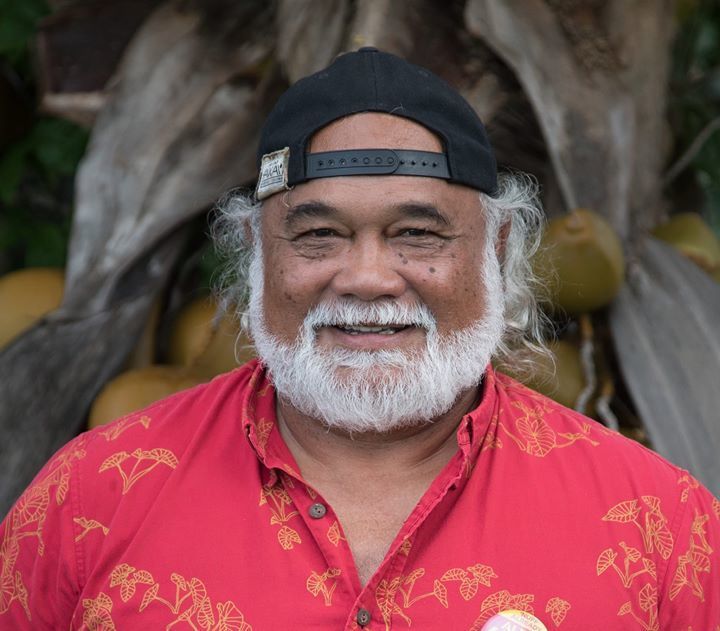

As Native Americans protest to protect their ancestral waters in North Dakota and are met with tear gas and militaristic suppression, water protectors in Maui have taken to the ballot box to elect Alika Atay, the island’s leading Native Hawaiian earth justice advocate, to their County Council.

An organic farmer and the grassroots leader of the statewide Aina (earth) Protector’s United effort, Atay had no prior political experience. Yet on November 8, he scored a dramatic victory late in the vote-counting night. As Atay described in an email to supporters the following day, “The 4th printout showed that we had lost by 259 votes and I was ready to concede, so we pule (prayed) and sang Hawaii Aloha. Then we got call that they did not count the 2000 ballots from Haiku, which is my country. We gathered everybody again and pule and sang Hawaii Aloha & Doxology (liturgy). Then we got a phone call saying that we won by 808 votes. We said that Po’ohala (my late son) had a hand in it. He asked Akua to let his daddy win; and win by 808 votes.”

With a total of 23,320 votes, Atay won the election by exactly 808 votes. In one of the synchronistic coincidences that seem to accompany Atay’s earth based Native Hawaiian spiritualism, 808 is both the Maui’s area code, and a numeric symbol of infinity.

Atay’s victory was a stunning upset to Maui’s Monsanto boosting power establishment, which had run Dain Kane, a four term former Council member who one activist called “a polished corporate front man” to oppose him.

As I wrote last month in a story about this important election here, Maui and the other large Hawaiian islands are the epicenter for GMO testing by the world’s largest agrochemical companies. According to the Center for Food Safety, “In 2014 alone, 178 different GE field tests were conducted on over 1,381 sites in Hawai’i (vs. only 175 sites in California). Herbicide-resistance was the most frequently tested trait in GE crop field tests.” This means that Hawaii’s vibrant land is regularly sprayed by massive quantities of dozens of types of pesticides (sometimes in combinations never before tried) on experimental GMO seeds to see what survives.

Atay has been the lead plaintiff in the SHAKA Movement’s federal lawsuit against Monsanto that I created this “Stop the Monsanto Doctrine from Poisoning Democracy” petition for here and which I wrote about here. The lawsuit, which is described in a two minute animated video at the bottom of this page, sought to enforce a GMO Moratorium that a grassroots group of Native Hawaiians, earth activists, parents and farmers passed in Maui in 2014.

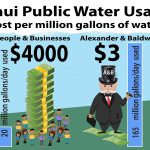

During an interview after his election victory, Atay explained that his concern for the GMO test farms involves their impact on the ecology, “I believe this is about water and the pesticides that affect water. I am concerned with the drenching of our land with pesticides and the effect this has on our water.

“I stand to protect our drinking water. We are very similar to my brothers and sisters in the Dakotas fighting to protect the Missouri River because Ola Ka Wai: Water is life.”

“We all have a responsibility to stand up for future generations. The importance of native water rights and the Aina Protectors movement is to allow those of us who are of the Aina to understand that this is our indigenous right that we are born with. We need to stand up and say enough of the oppression.”

Atay’s Election Part of Shift in Maui’s Environmental Politics

Unlike the State of North Dakota, which is responding to Native American water protector demands by assisting a private army with armored vehicles, militarized troops, rubber bullets, vicious dogs, tear gas, and water cannons in sub-zero weather, the County of Maui is allowing democracy, and its native leaders, to transform the island’s plantation-era legacy of water theft and agrochemical devastation.

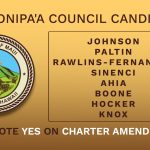

Atay was one of nine Council candidates who ran on the grassroots, Bernie Sanders-style Maui Ohana (family) slate of populist candidates that supported responsible environmental stewardship, organic, pesticide-free agriculture, attainably priced housing, and equitable water distribution.

Four of the Maui Ohana candidates won the election, increasing the number of GMO-resistant legislators by two, and coming close to a five person pro-environmentalist majority on the nine member County Council. In terms of the island’s balance of power, equally important was that Elle Cochran and Don Guzman, the top two vote getters for the Maui Ohana slate, won their races with 20% more votes than the top two vote getters from the island’s powerful political establishment. The number of citizens who voted for Cochran and Guzman was 20% (or 5,000 votes) greater than the number of people who voted for the two establishment incumbents who won reelection. In an outcome indicating a seismic shift for the county’s future, the Maui Ohana slate incumbents won the at-large election by a victory margin three to five times higher than the winning margin of the two establishment incumbents.

The significance of this historic victory for Maui Ohana was entirely ignored by Hawaii’s corporate media establishment. In its coverage here (which is behind a pay firewall), the Honolulu Star Advertiser, the state’s only large newspaper, never mentioned the Maui Ohana slate. Nor did it report the most significant political takeaway from the election: that the Maui Ohana incumbents won the election by 20% more votes than the establishment incumbents.

Instead, the Star Advertiser reported that East Maui incumbent Robert Carroll, who won by 11 points, “far outpaced educator Shane Sinenci,” while Lanai incumbent Riki Hokama, who won by only 7 points (23,270 to 19,091), “trounced Gabe Johnson.” Meanwhile, the Star Advertiser reported that in the Kahului race, incumbent Don Guzman merely “defeated” opponent Vanessa Medeiros. Yet Guzman won the race by a whopping 31 points, 30,762 to 13,786. That was more than four times the margin with which Hokama “trounced” his opponent.

People Power Fueled Atay and Maui Ohana Slate

Like Bernie Sanders’ campaign, which won more than 70% of the primary votes in Maui, the Maui Ohana slate was assisted by low cost people powered media that allowed thousands of grassroots supporters to share stories and political information across social media and emails.

Mark Sheehan, who for 30 years has been one of Maui’s leading grassroots leaders, was a leading fundraiser for the Maui Ohana effort. Sheehan believes that this election marks a long overdue shift in the County Council’s corporatist direction. “This election was very significant because each of our nine endorsed candidates garnered almost 20,000 votes. So even those who didn’t win will be stronger next time,” he explains. Within two years, Sheehan believes, Atay may even mount a successful challenge to Maui’s outspokenly pro-Monsanto mayor. “Alika’s voice will shake up the sleepy chambers on the 8th floor of the county building,” Sheehan said.

“We live on an island and must protect our sacred water.”

With his powerful deep voice and commitment to Aloha (love) focused leadership, Atay intends to bring a new earth protector direction to the Maui Council’s water and agriculture policies. “We live on an island and our job is to protect this aquifer, our sacred water. It is our only source of drinkable water,” he said. “There is a wave of momentum for change to protect our Maui way of living. Everyone sees the handwriting on the wall and is concerned with protecting the environment, which also protects our tourist economy. .”

Drawing from his Native Hawaiian tradition, Atay mixes allusions to a larger picture with Bernie Sanders style calls for civic engagement. “There are many prophesies of our ancestors,” he said. “Right now, with this victory, we are setting the cornerstone of the house that we want to live in. It is up the rest of the village to be involved in the construction of the house. I am looking forward to setting policy, regulations and enforcement that will protect our natural resources. We need our entire village to be involved to solve these problems.”