For generations, the myth that what was good for the Alexander & Baldwin corporation was good for the residents of Maui allowed Hawaii’s largest plantation and land development corporation to justify its legally questionable, ecologically destructive diversion of most of the fertile island’s largest streams.

During the late 19th century, after a handful of powerful oligarchs like Alexander and Baldwin seized power from the Hawaiian monarchy through the “Bayonet Constitution,” A&B developed an elaborate ditch system diverting nearly all the streams in rain-rich East Maui and channeling the water to more than 30,000 acres of plantation land in West Maui. The diversion system has nearly driven indigenous stream life to extinction and deprived Native Hawaiian farmers from growing the historic crops that had sustained Maui for centuries.

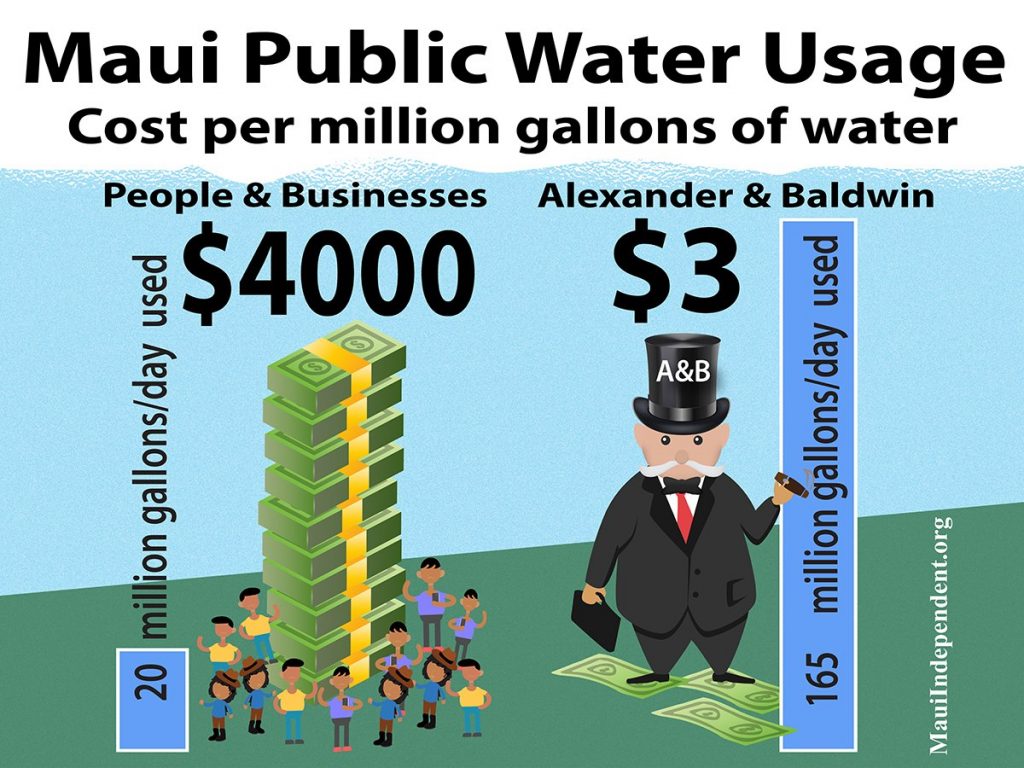

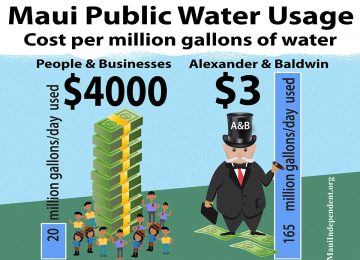

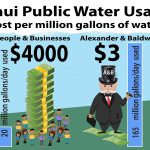

Instead of paying market rate for the water from public lands and sharing the proceeds with Native Hawaiians, as required by state law, for decades A&B has taken more than 80% of all public water consumed on the island (this means all water not supplied by private wells). That’s 165 million gallons a day, at an outrageously discounted cost of just $160,000 per year, or $3 per million gallons. Meanwhile, the island’s 155,000 residents, as well as those businesses and new small farmers that require public water, pay $4,000 for 1 million gallons of county-treated drinking water (with volume discounts for large users that reduce this to $1,100 per million gallons) –and some have to wait up to 20 years to access it.

In keeping with the new Maui Independent’s mission of Informing to Empower, our first petition, Stop A&B’s Massive Corporate Theft of Hawaii’s Protected Waters, can be signed on our What You Can Do section on the right of this page, or read in full and signed here.

Litigation challenging A&B’s massive water diversions began more than 20 years ago, resulting in a series of state court decisions that concluded, in a ruling in January 2016, that A&B’s water leases were indeed illegal. Instead of complying with the court, A&B, which is by far the largest donor to state politicians in Hawaii, went to the state legislature and in 2016 convinced them to pass a special law making their illegal activities legal for the next three years.

Last year, A&B closed its sprawling 32,000 acre sugar plantation which, despite using most of the island’s public water, contributed, through the constant cane burning of atrazine-laced crops, most of Maui’s industrial pollution, but less than 1/2 of 1% of its tourist-rich economy.

Earlier this year, despite the closing of the plantation and despite the fact that, as Maui’s Sierra Club has reported, ”documents submitted by A&B indicate there are 132 million gallons per day available from their existing private sources,” A&B began a duplicitously complex process to win approval of a controversial 30-year extension of three-quarters of their massive water diversions from the state’s corporate-friendly resource and water commissions.

The proposed lease would resume the delivery of 115 million gallons of water a day to A&B’s 32,000 acre former sugar plantation land, about six times more than all the treated public water consumed by all the people and businesses of Maui. The arid land, made valuable by a no-strings attached water lease, would be subleased to major agribusiness corporations, with some sold off by A&B as developments with multi-million dollar estates.

Because A&B owns the dozens of ditches that divert hundreds of streams across Maui, and because it also owns the tens of thousands of acres of plantation land that the ditches deliver the water to, the company is pursuing a water auction process in which it will be the only viable bidder.

This deliberately rigged system provides the sort of political cover that A&B has used for decades to disguise the inconvenient truth that it plans to continue paying a fraction of 1% of the fair market value of the water, which, even at the County’s volume discount rate, would amount to over $40 million annually.

But times are changing in Hawaii, even for A&B. Fueled by a new era of transparency and accountability brought about by indigenous and environmental rights activists, as well as people-powered new media, ever-growing waves of change have been washing against the shores of Maui for three years now.

As described here, a grassroots political movement of Native Hawaiians, environmentalists, farmers and parents joined forces in 2014 to oppose Monsanto and pass a GMO Moratorium initiative. But the power of the Hawaii’s agrochemical industry to pollute without local regulation was greater than Maui’s democracy. Monsanto, allied with Maui’s pro-GMO mayor and County Counsel, won an injunction in Federal Court effectively invalidating the initiative. Maui now has the dubious distinction of being the only county or state in the nation in which a publicly passed ballot initiative was blocked by a federal court.

Last year, Bernie Sanders and his populist Second American revolution fired up public interest activism on Maui, where Sanders received more than 70% of the Democratic primary vote. More recently, last November’s election delivered an upset victory by four grassroots Maui ‘Ohana (“family”) County Council Members, who have all lined up against a handout of public water for one of the state’s richest corporations.

Unlike the local officials in North Dakota who opposed the Lakota people’s Standing Rock uprising with a militarized army of police and mercenaries, the people of Maui have voted a new breed of grassroots representatives to power. The island’s young leaders are willing to challenge the once unchecked power of the “old guard,” and to blow the whistle on the rigged agrochemical and land development scheme that has dominated the state for decades.

Elle Cochran, the fiery Maui Council Member whose re-election in November garnered 25% more votes than any member of Maui’s old guard establishment, believes that A&B is telling the public and government one thing about diversified agriculture, and telling their investors another thing. “I want to make sure A&B understands that all of us haven’t quite bought into their picture,” Cochran says. “This is an investment is in our future and our children’s children future. It’s in our power to hold them accountable. To me this it has not been a transparent process and I am in complete dissatisfaction.”

In a statement to the Maui Independent, Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard, who represents Maui in Washington and is Hawaii’s best known national leader, agrees, “Water rights are enshrined in the Hawaii Constitution, and it must be managed as a precious public resource.”

“For too long,” notes Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard, “the diversion of Maui’s streams and water have disproportionately negatively impacted Native Hawaiians, small farmers, and residents in rural communities. It’s time to right these wrongs and ensure that access to water is fair and equitable to all. Water is life. We cannot survive without it. ”

Kaniela Ing, a Maui member of the State House of Representatives, who helped support his family working on pineapple plantations as a teen, has led the grassroots resistance to A&B’s water theft in the statehouse.

Ing calls for an end to what he has called “plantation mentality” politics. “The A&B corporation is the largest campaign contributor in Hawai‘i,” he explains. “You can expect tens of thousands of dollars for your campaigns if you support A&B. We might be the only state in the country where it is easier to change the law in the legislature than to prevail in court. It was wrong for the legislature to approve an extension of holdover permits for A&B. The biggest problem in Maui is there is too much power in too few hands.”

Ing is joined by Maui’s popular populist County Council members in recognizing that the future of the island’s agriculture will depend upon whether A&B continues to receive vast amounts of public water at a tiny fraction of its market value while growing pesticide reliant, polluting mono-crops, or whether citizens and their elected representatives can transition to a system that benefits the public, Native Hawaiians, and the island’s fragile ecosytem.

“A&B takes more than half the water on Maui,” Ing says. “There’s something wrong with that much power. If we’re serious about renewable, diversified sustainable agriculture, we’re going to have to break the plantation into small plots and allow small farms to pool resources, to support agricultural parks. If you allow the market to play out, A&B will lease land to other large landowners. So how do we encourage small farmers? We’re going to need some serious political disruption in order to do that.”

Mark Sheehan, a leading grassroots activist (and contributing editor of the Maui Independent), believes that “the fight for east Maui water is our Standing Rock. We are the Standing Rock of the Pacific.”

Tiare Lawrence, a passionate Native Hawaiian political leader who ran for Senate last year and nearly won, believes that the enormous “100 year storm” that hit Maui this winter was an omen of the times. “The rains that happened this past week are a clear indication that Maui needs cleansing,” she said at a public meeting early in January. “Here in Hawai‘i there is a history of insider backroom dealings that people are clearly frustrated with.”

Maui’s new County Council Member Alika Atay, a passionate outspoken organic farmer, anti-GMO activist and leader of the ‘Aina (earth) Protectors United effort, now heads Maui’s water resources committee. Atay believes that, “the end of the plantation era brings an opportunity for native water rights. We are very similar to our brothers and sisters in the Dakotas fighting to protect the Missouri River because Ola Ka Wai: Water is life.”

“We all have a responsibility to stand up for future generations,” Atay says. “This is our indigenous right that we are born with. We need to stand up and say enough of the oppression. Water and earth protectors: Maui needs you.”

Atay says that a group of Native Hawaiian families are reviewing their legal remedies to water rights and unpaid profits from the past, as well as claims on some of A&B’s sugar plantation land.

First year Maui Council Member Kelly King, an articulate eco business leader who co-founded Hawaii’s fast-growing Pacific Biodiesel corporation, believes that historic claims may open the way for dramatically more empowered negotiations with A&B over water rights,

“If you go back and you look at the rights of the Hawaiians and actually what’s owed to them by A&B,” Councilmember King said, “you could probably buy that whole system and most of that land with the money that they actually owe to the beneficiaries.”

Among the many similarities between the struggle of the water protectors at Standing Rock and in Maui is the surprising leadership of indigenous teenagers. Maluhia Stoner (whose name means peace in Hawaiian) spoke with compelling conviction at a crowded pubic hearing in which nearly everyone opposed A&B’s water lease extension.

“Nature has taken the waters of life from you because you have the nerve to abuse such a sacred element,” the 15-year-old Hana High school sophomore said. “You have already deprived our culture of the once abundant source of life and you dare take more. I testify that the East Maui Irrigation Company and A&B is guilty for the theft of our culture and the endangerment of native and indigenous species, the choice to ignore the claims of the Hawaiian people, the people of this island, and the destruction of the home in which we will always and have always resided.”

“The biggest distorter of the free market are monopolies,” Representative Kaniela Ing explains. “I think when it comes to the water supply there shouldn’t be one corporation controlling it because they become more powerful than the government and we have to do their bidding. Where misdeeds are being exposed, all of a sudden, we are told it’s ‘not Aloha.’ That’s a convenient response–and it’s oppressive.”

“The ruling class always says the sky will fall if we change things,” Ing concludes. “But we cannot let their fear tactics impede our progress.”